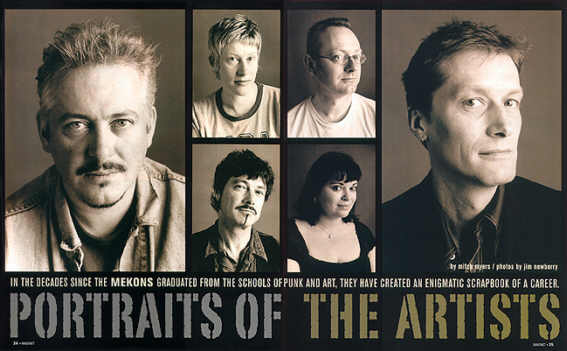

Who, or maybe what, are the Mekons? It's a fair question. One thing the Mekons are is misunderstood. Not by everybody and not all the time, but there's a certain element of confusion surrounding the Mekons gang. And they are a gang -- that is, a coterie of artistic renegades who have survived the music business for more than two decades. Of course, they're not exactly the same batch of literate art students with a socialist bent and a fumbling-yet-rousing aesthetic that emerged from Leeds, England, in 1977 at the dawning of the British punk explosion. Or are they? The Mekons have traversed the perilous realms of white reggae and dub, explored avant-rock and experimental electronica and reached deep into the history of American country music.

During the jagged course of their development, the Mekons have produced 20 albums, a notable art exhibit and accompanying book, a cooperative theater piece with visual artist Vito Acconci and a truly depraved rock opera with post-punk porn-feminist Kathy Acker. But these facts merely scratch the surface, and analyzing them is akin to peeling layers of an obtuse onion. Will speaking to the band and its peers provide some insight? It's worth a try.

Let's begin with Sally Timms, the British expatriate who resides in Chicago and has been lending her distinctive voice to the band since the mid-'80s. Are the Mekons misunderstood? "People are kind of confused by the Mekons, but sometimes I feel confused by the Mekons, too," she says. "There's so many different people involved that it has this life of its own, and it's a hard thing to get a handle on sometimes."

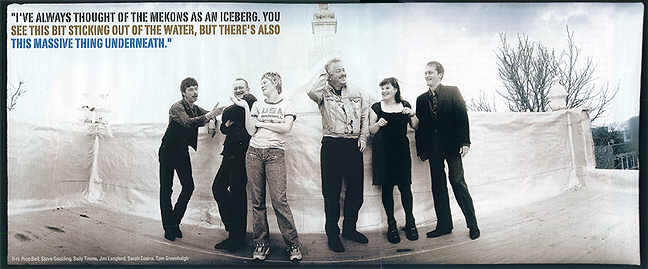

Among other things, the Mekons might be considered iconoclasts for those who think life in a rock group revolves around making albums and touring the country. Certainly, the Mekons do record and tour, but they only see each other one or two months a year. Residing separately in London, Chicago, San Francisco, New York and Leeds, they have managed to continue making music and, more importantly, remain friends. "That's almost the point of it," says singer/guitarist Jon Langford. "We can all go off and make albums on our own. I think we all see there's something special about doing work with a group of people that large and diverse."

Despite geographical restrictions, a series of music-industry hassles and the perennial lack of funding, the band's artistic labors have continued to evolve and inspire. Its latest album, Journey To The End Of The Night (Touch and Go), features an expanded lineup of veteran Mekons and can be considered a return to form by a classic band that plainly refuses to give up. With Welshman/Chicago resident Langford and London-based singer/guitarist Tom Greenhalgh at the helm since its inception, the group enjoys a minimum of six members and has remained resolutely mutable for the last 15 years. Whatever the Mekons are, the nucleus of Langford and Greenhalgh is still a creative force. "Tom and Jon were in it from the start, and that's something you can't get away from," says accordionist/singer Rico Bell. "No decision can be made without either of them."

But where exactly did the Mekons come from, and what were they doing in the first place? Hailing from the same Leeds art school that spawned punk-rock leftists Gang Of Four, the original Mekons had a revolutionary bent that quickly transcended punk's three-chord sloganeering. "Their early shows were a communal musical hub and seemed to involve everybody in the room," recalls original Gang Of Four bassist Dave Allen. "It was definitely non-exclusionary and very much part of what the punk scene was about. The Mekons understood that you couldn't separate art from politics. Politics was everything you did. When Gang Of Four, the Mekons and Steel Pulse would play on the backs of trucks in London to support Rock Against Racism, that was a more apparent politicization of the movement. But the Mekons understood that music, art, politics -- it's all one thing."

Not surprisingly, this all-inclusive nature still figures prominently in the band's outlandish live shows. There's something dangerously uncertain about a Mekons concert -- it's been that way from the beginning. Terrie, guitarist for Dutch punk-anarchists the Ex, recalls his first meeting with the Mekons in the early '80s. "We were at this festival, and the Mekons invited us and another band onstage," he says. "There were 40 people up there. Musically, it was OK, but the whole spirit of having such a good time and completely sharing it with everyone made a big impact on our ideas of music and bands. They think for themselves and aren't concerned about fashion or the press or anything."

In recent years, the irreverent stage spiel and bawdy rapport between Langford and Timms have become the stuff of hilarious (and often drunken) legend. Beyond the burlesque, Langford and Timms -- along with Greenhalgh, Bell and the rhythm collisions of drummer Steve Goulding and bassist Sarah Corina -- usually add up to an extremely entertaining evening, but not always. Because of additional presence of string master Lü Edmonds and violinist Susie Honeyman is a luxury the Mekons can't always afford, they still rely on roadie Mitch Flacko to join in for a song or two, evoking the exuberant camaraderie of their rousing punk days. And so it goes: The Mekons work with whatever they have available. "The live shows are dense because everyone gets so excited and they all want to play at once," says Honeyman. "It's not always such a good musical experience, but it's a different kind of experience."

"I don't know if we get it," says Goulding. "A lot of the times when we're onstage, I don't know what the fuck Jon is talking about. It's unpredictable in a way that music really isn't anymore. When you usually go to see a gig, you can rely on a certain level of professionalism and you can't see the inner workings of it. We're not really like that. You can see all the cogs working away. Sometimes the cogs need oiling and sometimes the cogs get oiled a little too much."

Goulding is democratic in his appraisal of the Mekons, spreading blame and credit for their live shows evenly. "It's like Freud's id, ego and superego, but I'm not sure which is which," he laughs. "Tom is the cerebral one, the brain. A tour without Sally would lose that acid-yet-sentimental quality she's got. Jon is the quintessential frontman. I think he's definitely in the same line of great Englsih music and comedic traditions as John Lydon, a showmaster who's also in the engine room providing direction."

What holds the Mekons together after all these years? Is it art? Booze? Sex? Politics? The music? Perhaps they haven't broken up because they're hardly ever all together in the first place. Edmonds, who lives in London and also plays with Billy Bragg, has his opinions regarding the Mekons' perseverence. "Maybe the band is just becoming more ornery and determined, refusing to stop," he suggests. "It's not easy; it's all done by the skin of the teeth and the seat of the pants. Every person is doing lots of different things, yet there's this bizarre, unnatural bond between us and it calls us back. We just do it with very little expectations and are lucky to have this existence on the periphery of the rock 'n' roll world."

On

Journey To The End Of The Night, the Mekons compensate for the physical

distance between bandmates by patching together separate perfomances from

studios on both sides of the Atlantic. Relying on digital-recording

techniques and ProTools computer software, the band loses some of the immediacy

of its live performances but gains greatly in careful craftsmanship and

mature songwriting. The only thing this technology really means is

that the old guard is still finding new ways to create music together.

Even founding Mekon Kevin Lycett, who quit the band long ago, provides

lyrics for the album.

On

Journey To The End Of The Night, the Mekons compensate for the physical

distance between bandmates by patching together separate perfomances from

studios on both sides of the Atlantic. Relying on digital-recording

techniques and ProTools computer software, the band loses some of the immediacy

of its live performances but gains greatly in careful craftsmanship and

mature songwriting. The only thing this technology really means is

that the old guard is still finding new ways to create music together.

Even founding Mekon Kevin Lycett, who quit the band long ago, provides

lyrics for the album.

Greenhalgh believes the Mekons have been energized by modern recording methods. "It gives us a lot more flexibility," he says. "You can approach things from an intellectual perspective and think about what you're doing. Then, you have the technological wherewithal to actually make what it is you're thinking possible."

Ironically, Greenhalgh's role in the Mekons is often overlooked. Usually home in London while Langford and Timms are working in the U.S. (the former with the Waco Brothers and the latter pursuing a solo career), Greenhalgh's contributions are vital to the band's identity. "Tom is a really gifted musical person in an untrained way," says Timms. "He has an amazing voice; it's very emotional." Indeed, Greenhalgh's vocals on Journey's "Myth" are glowing and evocative. Somewhat resigned but still kicking against the pricks, he's the steadfast voice of the Mekons.

It was on their 1998 album, Me, that the Mekons first began using ProTools and other recombinant studio techniques. What they created was a cybersexual hodgepodge of synthetic rock 'n' roll. It was an electronic gang-bang of art and language that titillated some fans and disappointed others. "Me wasn't really about songs," says Langford. "It was a sonic thing. It was about working with ProTools. The lyrics were written by committee with several Mekons and some really drunk cousins of mine egging us on. People didn't know how to take that. I guess since we're from Britain, we still think cursing is clever. Sally has the voice of an angel and the mouth of sailor, so it went on like that. It was very electronic; the words were rigid and not touched by personal experience."

Mixed emotions toward Me were evident among the Mekons, and the subsequent recording of Journey became something of a reaction to those ambivalent feelings. "Sally said, 'Let's make a good album for a change, none of this crap,'" laughs Goulding. "We do work on a lot of different levels at a time. We're never going to get that successful, so we're just making music like normal people used to do a long time ago, sitting around in little villages. It functions as entertainment, telling a story and expressing what you feel about your world."

Langford also credits Timms for the band's back-to-basics approach on the new album. "Sally started the ball rolling by saying we should do an album with more simple songs on it," he says.

"We set out to make a completely different record than the last one, which we obviously did," says Greenhalgh. "It's just sort of curious that we could do that using the same studio, the same engineer and all the same team."

Besides, you can't judge the Mekons by looking at just one of their album covers. "I've always thought of the Mekons as an iceberg," says Greenhalgh. "You see this bit sticking out of the water, but there's also this massive thing sticking underneath that's part of the same thing."

Honeyman also views the group's immense body of work as deceptively complex. "I can't show people what the Mekons are like without putting on 15 different tracks," she claims. "It covers a vast area. We're all such different musicians with different abilities and styles. Yet, I think we do make this rather unique sound."

Another enigmatic aspect of the Mekons is their tendency to engage in project that stray far outside the typical rock parameters. Tje band's art retrospective, which debuted at the Polk Museum in Tampa, Fla., inspired a combination book and album, Mekons United, in 1996. It's a substantial collection of music, paintings, fictional text, social-political rhetoric, extended art analysis, twisted letters to home, drawings, photos and even diatribes by the likes of Greil Marcus and Lester Bangs. While Langford's comic fascination with the death of country music is explored in lurid visual detail and Bell's paintings are unusually stately, all of the artwork is selflessly credited to the Mekons.

For those who enjoy things a bit more risqué, there's the band's creative exchange with Kathy Acker. Pussy, King Of The Pirates was an unusual project, even for the Mekons. A musical adaptation of Acker's book, the Mekons recorded Pussy with Acker narrating her provocative fable between songs. Besides releasing Pussy as an album, the Mekons and Acker also performed the show together onstage in 1996. An audacious, salty sea tale, the live production of Pussy was radically charming, a blend of Marquis de Sade's The Story Of O and a high-school rendition of H.M.S. Pinafore.

Sadly, Acker succumbed to breast cancer two months after her collaboration with the Mekons. Greenhalgh spent some time with her in London before she died. "We knew Kathy as a friend, and she mentioned that she was completing this new book that had a lot of songs in it," he says. "It was blindingly obvious that we should do something with her. So we went in the studio, and she sent the songs. At one point, they were coming through by faxes while we were putting the tunes together."

There are so many different voices for the Mekons, so many different songs, innumerable ideas have turned into art and tangible action. There have been myriad live performances, plenty of festival sub-groupings and countless friends made along the way. Adding to the Mekons renaissance, Touch and Go has recently released a two-volume anthology, Hen's Teeth And Other Lost Fragments of Unpopular Culture. These outtakes, remakes and other brilliant mistakes go all the way back to 1980, serving as microcosms of the Mekons' many transmogrifications.

"We just have a lot of friends that trust each other," says Langford. "We cooperate and have managed to work out strategies to make the Mekons communal. People have their little areas of expertise, but nobody is that precious about what they bring to the table."

Maybe the Mekons aren't really misunderstood at all. Perhaps, in the final estimation, it just depends on whom you talk to.